With 2018 marking the 100th anniversary of Leonard Bernstein’s birth, a spotlight has again been placed on the composer’s fierce commitment to education, demonstrated throughout his life by activities like the Young People’s Concerts and his Harvard Lecture Series. It was during the latter that Bernstein emphasized the importance of “inter-disciplinary values,” explaining that “the best way to ‘know’ a thing is in the context of another discipline.”

This sentiment would eventually become the core of Artful Learning, an educational model that seeks to engage students at a deeper level by framing learning with the arts. In the early 1990s, Nashville became the unlikely home of the Leonard Bernstein Center for Education Through the Arts, which served as the headquarters for years of research and development for the Artful Learning model.

Why Nashville? Leonard Bernstein comes to Music City

In 1992 the New York Times ran a story on the center’s opening, spending several paragraphs essentially asking “Why Nashville?” After all, Bernstein spent most of his life living and working in New York City.

Bernstein’s son, Alexander, who continued spearheading the effort after his father’s death in 1990, defended the choice, saying that “people in New York, the rest of the country and the world” would “learn soon enough about the energy, involvement and commitment of [the Nashville] community and of its creative spirit.” He wasn’t wrong. A few decades later The New York Times would declare Nashville an “it” city.

In reality, though, it was one man who drew Bernstein to Music City. Before he would become Founding President and CEO of the Leonard Bernstein Center, Scott T. Massey was President of the Nashville Institute for the Arts, a teacher-training organization founded in 1979 and patterned after Lincoln Center’s educational programs. Massey recognized Bernstein’s lifelong commitment to education, and amidst debates on how to reform public schools, decided to approach Bernstein with the idea for a center in Nashville.

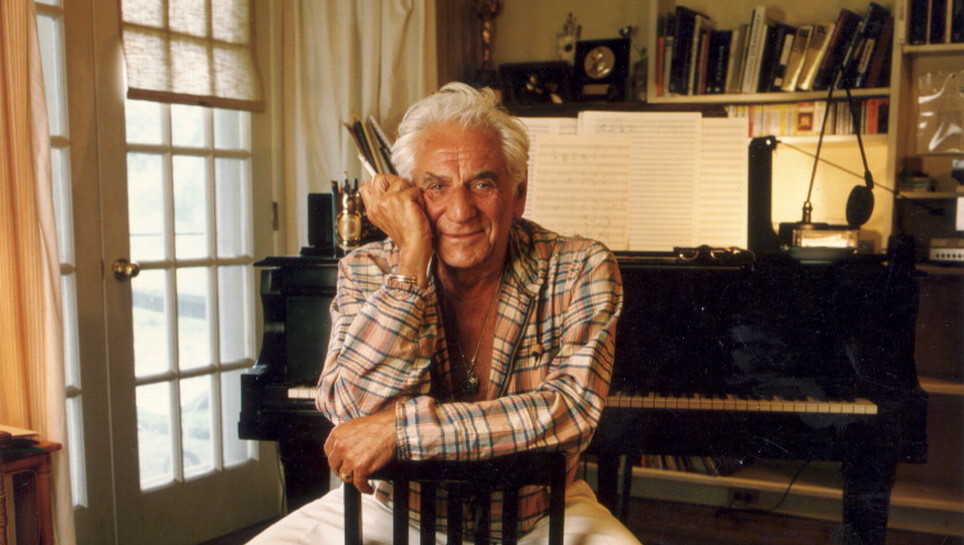

When I called Massey, who has since moved on from his work with the Leonard Bernstein Center, he remembered his first meeting with Bernstein fondly. He recalls hearing sounds of a piano and faint cursing as he approached Bernstein’s stables-turned-studio at his farm in Connecticut. Inside, Bernstein was wrestling with new IBM technology that was meant to transcribe a music score as he played. Apparently the technology couldn’t keep up with the composer, who responded with a dose of expletives.

Bernstein and Massey shared a vision for re-energizing learning with the arts. “Conceptually we really hit it off from the beginning,” Massey remembers, saying that the two talked well into the night. Over the next few years, which would also be the last of Bernstein’s life, the pair worked together and with academic research partners from Columbia, Harvard and Peabody College on the development of Artful Learning.

The Development and Early Results of Artful Learning

Pilot K-12 schools were chosen throughout Nashville to participate in the program, and Massey worked closely with Nashville teachers during the process. “We really believed that it was important to empower teachers and not to try to come in from the outside with an imposed solution,” he explains. “Instead we wanted to really put them at the center of the design and development process with us providing systems and ideas and insights.”

What resulted was what Massey describes as a “comprehensive school reform package,” complete with a three-year teacher training program, curricular and assessment guidelines, and a handbook on the process of becoming an Artful Learning school.

So what happens when the arts are totally integrated into the classroom? When music, dance and painting are used to teach science, history and math; when art is central to the curriculum instead of extraneous?

According to Massey, in short: “It works.” After participating Nashville schools underwent independent assessments, Massey said he saw “significant improvement” on standardized test scores, and perhaps more importantly, “there was a significant improvement in the motivation levels and attendance levels at every category.”

But reinventing education is not an easy task, nor one without critics. Over the course of the development phase, The Tennessean reported on tensions between Metro educators and the Leonard Bernstein Center. Some educators felt they weren’t getting clear enough answers about what the Center was all about. Some became frustrated with the amount of funding given to Nashville Institute for the Arts and the Leonard Bernstein Center, compared with the much smaller amount spent on existing arts and music programs throughout the Metro system. One teacher reported feeling overwhelmed by the daunting task of essentially reinventing her job.

Artful Learning Leaves Nashville

Now, 25 years after the Bernstein Center was established and after the city celebrated its opening with a flurry of star-studded dinners and events, there isn’t a single school in Nashville — or in the state of Tennessee, for that matter — that uses the Artful Learning model. A total of 17 schools in the country, most of them concentrated in the Midwest, are currently listed on the Artful Learning website.

Massey says it was most likely a perfect storm of events that lead to the departure of Artful Learning from Nashville schools. When the development of the program was complete, Massey was recruited for a position in Indianapolis, and decided to pass the Artful Learning baton to the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, a foundation Massey felt was better equipped to market the program nationally. As part of that negotiation, the Leonard Bernstein Center headquarters were moved out of Nashville and to Santa Monica, California in 1999.

Part of this shift from development to marketing also meant a change in the program’s financial model, Massey explains: “During the time I was involved, we were actually funding schools to do the program… we were investing charitable dollars that were raised for the purpose of creating the program in the schools.” After development was complete, the new financial model meant that schools would pay to participate in Artful Learning, although Massey points out that the program was structured so that schools could participate at different levels with different costs, depending on their financial situation.

Massey also cites a major change in Metro Nashville Public Schools leadership around this same time. Richard Benjamin, who was Superintendent during the research and development phase at the Bernstein Center, and who Massey describes as “incredibly supportive” of the endeavor, was recruited for a job in Atlanta. He is currently a Senior Consultant for ArtsNow in Atlanta, a company developing “research-based arts integrated professional training for educators.”

“So there was a change in leadership, a change in the model, and a move for the headquarters, it was probably a perfect storm of changes that contributed to it.” Massey summarizes.

Still, Massey hasn’t lost faith in the model, which reflected his and Bernstein’s deep belief that a good education is like the artistic process.

“Drilling people with data and facts is not the essence of a good education, but like an artist, the key is how to do you take all of this information, all this data, and create something out of it that has meaning and value at a higher level?” Massey says. “I still believe that this is the best approach to getting our public schools re-energized and really transforming the way people learn.”