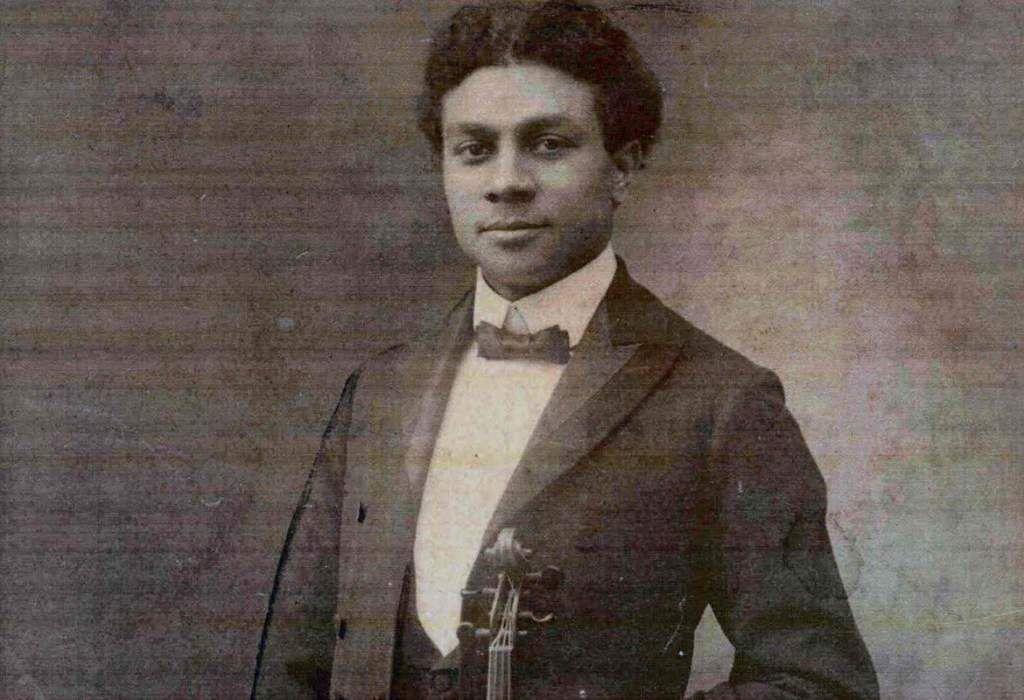

Browse the Visit Clarksville, Tennessee website and you’ll find the “Clarksville Connections” project. It’s a directory of sorts, showcasing significant people in the city’s history. Among the athletes, authors and inventors is concert violinist and composer Clarence Cameron White, who was born on this day in 1880.

White spent the first few years of his life living in Clarksville with his father James B. White, a doctor and school principal, and his mother Jennie Scott White, a conservatory-trained violinist. But when Clarence was just two years old, his father passed away and Jennie took Clarence and his brother back to Oberlin, Ohio, where her parents lived and where she had studied violin at the Oberlin Conservatory.

Given Oberlin was a community that welcomed Black students seeking higher education at a time when most conservatories did not, Clarence would also eventually study there. But it was an earlier experience at the conservatory that initially sparked his interest in music. He later wrote:

My mother took me to hear The Messiah sung at the conservatory and I came away humming snatches of it. Mother thought I had a good musical ear and persuaded my grandfather, who was a religious man, to give me his violin… I was only six at the time, nevertheless, my grandfather pouted. ‘I’ll give him the violin. But if he ever plays at a dance I’ll take it back.’

A second move to Washington D.C. exposed White to the rich cultural activities of the Black community there, and White began studying music with Will Marion Cook—after, he admitted, falling asleep at one of Cook’s violin recitals. Waking up to tremendous applause and realizing he had missed the performance, White says he began crying to such an extent that Cook inquired after him and then took him on as a student. It was during this summer of lessons with Cook that White made up his mind to become a violinist.

White would eventually blossom into the foremost Black violinist in the early 20th century. As a composer, White’s music evolved over the course of his career. Many of White’s compositions reflect a neo-romantic style, which much of his work (and nearly all of the recordings made of his music) center around his exploration of Black musical traditions, like the 1918 collection Bandanna Sketches: Four Negro Spirituals.

Only a few recordings of White performing his own music exist. He recorded “Lament (I’m troubled in Mind)” from Bandanna Sketches, with Black Swan, the first major Black-owned record label founded in 1921 for the exclusive promotion of Black artists.

Here, violinist Igor Kalnin and pianist Rochelle Sennet give a modern-day performance of the same piece:

The opening movement from Bandanna Sketches, “Chant,” employs the familiar spiritual melody “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.” While originally written for solo violin and piano, the piece has also been arranged for larger ensembles, like this version performed by the Paragon Ragtime Orchestra:

Still, so much of White’s music remains deserving of more attention. His 1932 opera Ouanga!, composed after White took a six-week trip to Haiti, chronicles the rise and fall of Haitian revolution leader Jean-Jacques Dessalines. It hasn’t been performed since 1956, though it remains one of Whites major compositional achievements—and gives a unique perspective of the Black Atlantic diasporic experience.

In addition to composing, White continued to tour as a recitalist throughout his lifetime. His concerts, which often included his own music and a mixture of sonatas and salon pieces, were highly praised by critics. At one 1947 recital, White played Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 2, Op. 30, his own Violin Concerto in G minor, as well as a number his own shorter works like “On the Bayou.”

White wasn’t the only one performing his music— two of the biggest violin virtuosos of the era, Fritz Kreisler and Jascha Heifetz, programmed White’s music in their concerts. Heifetz even recorded White’s piece “Levee Dance.”

As scholar Alexandra Kori Hill points out, Heifetz’s performances of White’s music must have been a double-edged sword for the composer. On one hand, his music was being performed, and by one of the most respected violinists of all time. However, these performances did not contribute to White’s success in the mainstream classical world.

Despite elusive mainstream success, White carried on a richly diverse musical life. In addition to his work as a composer and performer, White was a teacher and writer, contributing articles to The Negro Music Journal in the early 1900s, and serving as faculty at West Virginia State College, Hampton Institute, and the Washington Conservatory of Music, a private institution that trained Black musicians.

Between 1922-1924, White also served as the president of the National Association of Negro Musicians, an organization for which he was a founding member.

Tune in to 91Classical throughout the day to hear more music by Clarence Cameron White.