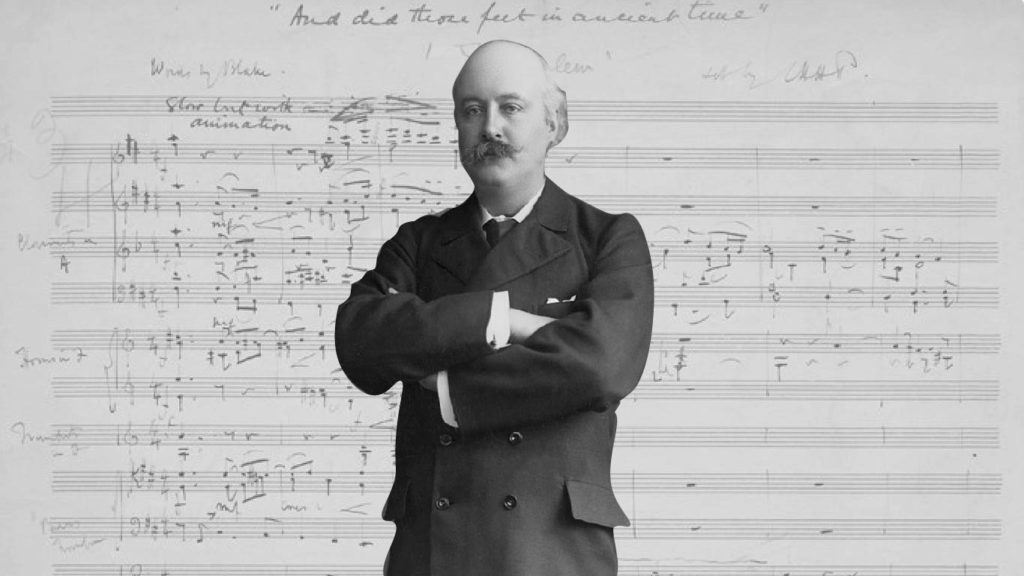

For all of Europe, and eventually the world, the events of the first World War were devastating as they unfolded. Over just four years the population saw unprecedented death and destruction. English composer Hubert Parry did not reach the armistice, as he died just a month before. But during those difficult years he composed his Songs of Farewell – six motets that collected deeply meaningful poetry from across the United Kingdom.

Read more: 91Classical continues to celebrate National Poetry Month.

Parry was director of the Royal College of Music during the war, and the losses that the school faced were particularly painful. In a letter to fellow composer Herbert Howells, Parry said, “The thought of so many gifted boys being in danger […] is always present with me” as many of his students were moved from the classroom to the trenches.

The collection acts as a final testament from a great composer who was disheartened, both figuratively and literally. By the time the complete set premiered in 1919, Parry had died, the war had ended with the loss of 40 million people, and a flu epidemic raged on across the world.

My Soul, there is a country

A poem called Peace is the first in Parry’s set. Poet Henry Vaughan wrote it in 1650 as part of a collection called Silex Scintillians – one of the great works of English literature in the 17th century. The “peace” from the title does not refer to peace on earth, or even as state of peace at all, but rather refers to God sitting in heaven.

My Soul, there is a country

Far beyond the stars,

Where stands a winged sentry

All skillful in the wars;

There, above noise and danger

Sweet Peace sits, crown’d with smiles,

And One born in a manger

Commands the beauteous files.

Welsh writer Stevie Davies describes Vaughan as trapped in a bellicose world, living in Wales during the English Civil War. Davies labels the Silex Scintillians as a work composed in in protest during great emotional distress – much like Parry’s Songs of Farewell.

While “Peace” relies on simple language and imagery, Parry’s setting finds the emotion of every sudden outcry and surprising exclamation. An especially moving one seems to come midsentence – as the choir even holds a soft dynamic all the way until breathing together and exclaiming “O my Soul awake!”

I KNOW my soul hath power

While Henry Vaughan was trapped in turmoil, half a century earlier Sir John Davies was an agent of political change. As the Attorney-General for Ireland under King James I, Davies added to the power of English rule and property allocation. And he earned that political clout through poetry – dedicating works to Queen Elizabeth I, as well as King James I. In the poem Man he shows a talent for self-deprecation.

I KNOW my soul hath power to know all things,

Yet she is blind and ignorant in all:

I know I’m one of Nature’s little kings,

Yet to the least and vilest things am thrall.

In Parry’s setting of the poem, the bitter irony of every statement is found most sharply in the final line, as the choir punctuates “Man” with a bright chord. But then seemingly falls apart over the phrase “and yet…” – the only line where the voices move separately for the whole movement, before ending on a timid pianissimo “wretched thing.”

I know my life ‘s a pain and but a span;

I know my sense is mock’d in everything;

And, to conclude, I know myself a Man—

Which is a proud and yet a wretched thing.

Never weather-beaten sail

Thomas Campion is the first English poet to make an appearance in Parry’s set. Many of Campion’s poems were written with the intention of setting them to music. As he said, “What epigrams are in poetry, the same are ayres in music, then in their chief perfection when they are short and well seasoned.”

At the time, a career in law went hand in hand with work in the arts, and it was Campion’s time in law school at Gray’s Inn that actually allowed him to get to know many other writers and musicians who resided in St. Dunstan’s In-The-West. While he eventually began working as a physician, he also started to publish poetry. Campion was not particularly old in 1613 when he published his second Book of Ayres, which includes Never Weather Beaten Sail. But, he was only seven years away from his own sudden death, now thought to be of the plague.

Never weather-beaten sail more willing bent to shore,

never tired pilgrim limbs affected slumber more,

Than my weary spirit now longs to fly out of my troubled breast:

O come quickly, sweetest Lord, and take my soul to rest!

Like Campion’s approach to poetry, Parry’s take on this Never Weather Beaten Sail is more lyrical than those that precede it in the set, as the individual lines of poetry are more connected than before. Parry adds a fifth voice, allowing for even more motion within the parts. This addition (or, splitting of parts) continues through the rest of the Songs of Farewell, until the final movement is for eight parts – two whole choirs.

There is an old belief

Poet John Gibson Lockhart represents Scotland in Parry’s collection. He is also the youngest of the poets in these settings, being from the 1800s. Lockhart was best known as a biographer, including that of his father in law, Sir Walter Scott. He was also greatly affected by bereavement through the later part of his life, which resulted in his own health eventually failing. One by one he lost most of his children and his wife in just a few years. It was just after this string of losses when, in a letter to a fellow writer, he composed There is an old belief.

There is an old belief

That on some solemn shore

Beyond the sphere of grief

Dear friends shall meet once more.Beyond the sphere of Time and Sin

And Fate’s control

Serene in changeless prime

Of body and of soul.

The most serene of settings in this collection, Parry allows phrases to repeat themselves in flowing lines from the singers. The dynamics do change, but never in the terraced fashion of the previous movements. However, much like the credo movements of old masses, Parry does put the choir’s motion back together for the final stanza, which begins “That creed I fain would keep.”

At the round earth’s imagin’d corners

The poetry of John Donne, while well-respected in his time, had fallen out of favor for centuries before its rediscovery in the 1800s. Now his place on lists of great English poets and writers is assured, and few poetry classes can end without a look at one of his works.

Maps in Donne’s time were drawn with angels at the corners, so while he knew the earth was round, it was still easy to imagine where four heralds could be positioned on Judgement Day. The poem begins with a speaker ready for this biblical moment to occur.

At the round earth’s imagin’d corners, blow

Your trumpets, angels, and arise, arise

From death, you numberless infinities

Of souls, and to your scatter’d bodies go;

But the speaker realizes that he does not want to hasten the apocalypse. As he muses on who shall rise, he realizes that he wants to mourn these losses. And he himself may not in fact yet be worthy of heaven.

For if above all these my sins abound,

‘Tis late to ask abundance of thy grace

While this setting brings in touches of chromaticism and exciting, sweeping motion, it also uses very apparent text painting. “Blow your trumpet” is repeated with bright thirds and leaping octaves. Voices leap upward in fourths and fiths with “and arise.” And just before the speaker’s change of heart, these fanfares fade away, to a quiet fermata. “But let them sleep” is downright timid, before the reason, “tis late,” is delivered with a touch of “agitato.”

Lord, let me know mine end

Parry ends with text from the King James Bible, in a climactic setting of Psalm 39. The final movement of Songs of Farewell is a tour-de-force. With eight parts, Parry is able to have two choirs respond to each other, or eight voices sing in thick harmony together, and move individually in a dizzying display of polyphony. And he takes advantage of every possible texture. The most poignant moment of the whole set arrives just before the very end as Parry, who knew of his own heart condition, sets a request for just a little more time on earth.

O spare me a little, that I may recover my strength before I go hence

And be no more seen.