For some musicians, entering the field seems predestined. Multiple generations of talent combined with growing up around an impressive set of performances can set one on the path to a fruitful career. For John Wesley Work III, three generations of professional music-making led to a comprehensive collection of spirituals recorded for posterity, as well as a substantial repertoire of new compositions during his career at Fisk University.

John Work II

John W. Work, who had been born into slavery in Kentucky, was a church choir director, whose members were part of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers. His son, John Work II, worked as a teacher in Tullahoma, Tennessee, before taking a position teaching Latin and history at Fisk, where he also helped in the music department. As a historian, Work II and his brother Frederick joined forces to document Negro spirituals and publish them, including two collections in the first decade of the 20th century. One of those collections included the song Go Tell It On The Mountain, a song which featured as heavily in the civil rights movement during the 1950s and 60s as it does today in Christmas church services.

In this performance from our Live in Studio C program, countertenor Patrick Dailey performs the song with Early Music City.

Because of financial difficulties, the Fisk Jubilee Singers became a quartet in the early 1900s. John W. Work, II was the tenor, and provided many of the musical arrangements. While in that position Work II grew frustrated with the use of the songs for fundraising rather than for their true meaning and artistry.

“In the early days it was looked upon as a curiosity in the world of song, beautiful, entertaining but transient, for the world never considered it more than a commodity, through which one or two Negro schools maintained themselves.” – John W. Work, II

This frustration combined with what he described as a growing animosity toward folk music at the university, Work II left his position at Fisk and with the Jubilee Singers in 1923, upon his son’s graduation.

For his own compositions, the best known is an art song called Soliloquy, featuring poetry by Myrtle Vorst Sheppard.

Not only was John W. Work III’s father a music historian, but his mother was also a singer who helped training the Fisk Jubilee Singers. After studying at Fisk and The Institute of Musical Art (which later became The Juilliard School), as well as later achieving degrees at Columbia and Yale, Work III began teaching at Fisk. The Fisk Jubilee Singers still perform his spiritual arrangements today.

John W Work III

Like his father, John W. Work III collected songs by traveling and attending church services in remote areas. He described the paradox of recording a folk song in an untitled manuscript, saying that no matter the skill of the transcriber, the singer was unlikely to perform the song in the same way each time, so it’s only possible to collect variants of a real song. This held true for both the notes and the dialect of the songs Work collected, which differed by region.

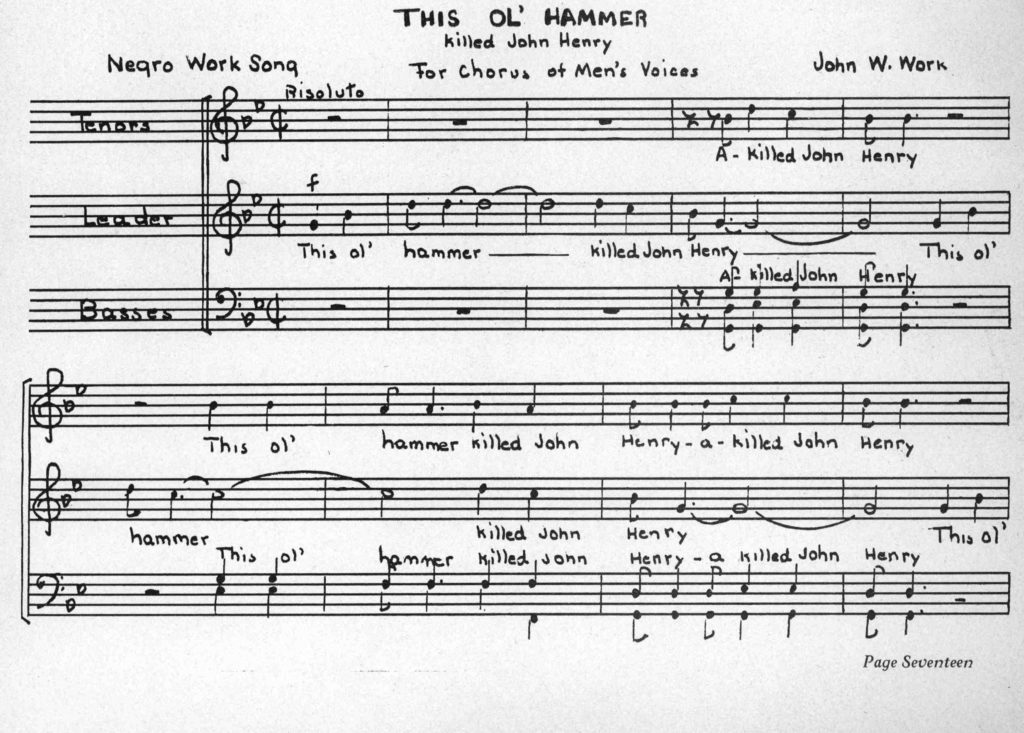

In 1940, Work III published his own collection of American Negro Songs which included 230 pieces of music. A most famous part of this collection was This Little Light of Mine, which like Go Tell It On The Mountain, became an important Freedom Song during the 1960s. Early Music City recorded the piece at a safe distance, during COVID-19-related closures this spring.

More: This Little Light of Mine, American Anthem

While his collection of spirituals and folk songs was cited in numerous academic journals, Work III maintained an interest in new musical styles as well. His research over the summers of 1941 and 1942 was done in the company of historian Alan Lomax. Along with Charles S. Johnson and Lewis Jones, Work III visited the Mississippi Delta to record and document that music for the national archive. The visit included a then-unknown singer named Muddy Waters. These field recordings are in the Library of Congress, including this recording of Po’ Boy A Long Way From Home, sung by Sunny Chastain.

He also documented the beginning of the use of the piano, which was new to rural African American music at the time given the expense of the instrument. Charles Ellis plays in this recording of a song called My Fat Hipted Mama.

As Gospel music began to emerge in African American church services, Work III saw the potential of this new musical form.

“… this type of folk music will continue to be used and even enjoy a greater popularity in time to come. The folk felt a stirring for a new music. They are busy creating it.” – John W. Work III

Work III had begun composing in high school, and eventually was the second John W. Work to direct the Fisk Jubilee Singers, creating his own arrangements for the choir, as well as publishing art songs.

His published pieces range from cantatas and tone poems to solo piano pieces like Sassafras.

As classical music prepares for its return to the concert hall in a post-COVID-19 world, with a renewed sense of responsibility to music’s diverse history, perhaps this is the time for composers like John W. Work III, who took the time to document the music of the Black communities across the United States, to have their original work in the long-overdue spotlight.

We’ll continue to feature the music of Nashville’s composers as we celebrate Local Composer’s Month throughout July. Find content on air and online at 91Classical.org.