Even though the spark of International Workers’ Day was lit in Chicago over 130 years ago, Americans are more likely to spend May 1st singing festive music around a maypole than shouting labor songs in a street protest.

And how Americans have responded to, embraced or rejected music created by classical composers around the labor movement echoes how the United States has reckoned with this holiday and all it represents.

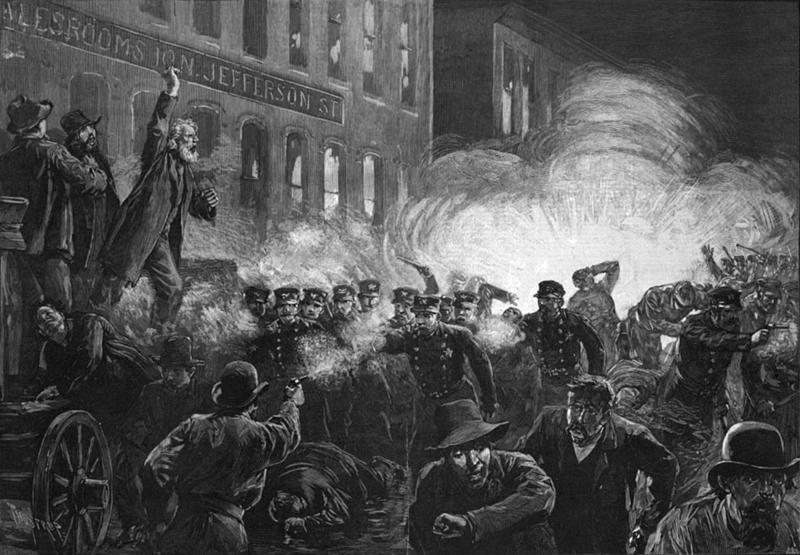

The Explosion That Sparked A Movement

The person who threw the bomb during a labor demonstration at Chicago’s Haymarket Square on May 4th, 1886 was never identified. But the act — which killed seven police officers, at least four civilians, and led to a controversial and sensational trial ending with death sentences for seven men labeled “anarchists”— had tremendous repercussions all over the world.

In 1889, the International Socialist Conference declared that May 1st would become an international holiday for labor to commemorate the Haymarket affair. Those in support saw the aftermath of the event as an injustice and continued to push for safer working conditions, higher wages, and a standard eight hour work day.

In the United States, anti-labor movements urged political leaders to create distance from the violence of Haymarket and the stigma the bombing had given to labor demonstrations. American opted instead for a more politically neutral celebration of labor on the first Monday in September.

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and consequent first “Red Scare” continued to fuel anti-communist sentiment in America, until in 1921 Congress pointedly designated May 1st as “Loyalty Day,” a day set aside for “the reaffirmation of loyalty to the United States and for the recognition of the heritage of American freedom.”

But that didn’t quell the expression of leftist sentiment in America, especially in the arts.

Classical Music Meets Politics

Ruth Crawford spent the 1920s studying piano in Chicago, and by 1932 had married fellow musician Charles Seeger. When the couple’s avant-garde approach to composition began to feel out of place in the post-Depression years, they became interested in political music, eventually joining a Composers’ Collective that was an offshoot of the Communist Party’s International Music Bureau.

While Charles wrote music criticism for the New York Daily Worker, Ruth penned political tunes, including “Chinaman, Laundryman,” a setting of Chinese-American author H.T. Tsiang’s poem about the plight of immigrant workers. To represent the class struggle, Crawford Seeger deftly contrasted the vocal line with a churning piano accompaniment.

The Seegers would later dedicate themselves to collecting American folk songs, and Ruth’s composing was cut short by cancer. But the torch of music and politics would be carried on by her folk musician children, including her stepson Pete Seeger, whose Communist convictions kept him under the watchful eye of the FBI and the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Though he’s credited with largely crafting the quintessential “American Sound” of the mid 20th century, Aaron Copland was also a target for “un-American activities.” Though Copland never officially joined the Communist Party, he mixed freely in communist circles: he dipped his toe into the same Composer’s Collective that Charles Seeger belonged to, tried his hand at “workers’ music” with a 1934 setting of Alfred Hayes’ poem “Into the Streets May First,” and openly supported Communist political candidates.

But unlike the Seegers, Copland gradually shied away from overt politics in his work, instead focusing on honing a musical style that was accessible to wider audiences. That didn’t save him from a confrontational inquisition during Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anticommunist hearings in 1953, or from the FBI spying on him for decades.

“I spend my days writing symphonies, concertos, ballads and I am not a political thinker,” he told the committee. The denial nearly earned him charges of perjury and fraud.

Still, even Copland’s later, more politically neutral work maintained a connection to the idea of the working class and leftist politics. In 1942, when then-vice president (and future presidential nominee of the left-wing Progressive Party) Henry Wallace gave a famous speech proclaiming the dawning of the “Century of the Common Man,” Copland found inspiration for one of the most iconic and beloved works of his career, Fanfare for the Common Man.

Copland’s contemporary Marc Blitzstein was far less shy about making politically radical music. His pro-union opera The Cradle Will Rockdepicted workers in the fictional setting of Steeltown, fighting for freedom against a greedy capitalist villain named Mister Mister. A young Orson Welles was set to direct the first performance on Broadway in 1937, until budget constraints led the Works Progress Administration to shut down the production a few days prior to the premiere.

Rumors swirled that the administration wanted to halt the production not because of budgetary reasons, but because of fears that the opera’s themes would cause violence to erupt in steel towns all over the country.

Blitzstein’s revolutionary spirit wouldn’t be hampered, and at the very last moment on opening night, the cast and crew marched to a vacant theatre twenty blocks north. To avoid government and union regulations, the cast of Cradle performed the opera from seats in the audience with Blitzstein at the piano.

The show was a hit with New York progressives, enjoying a sold-out run of performances. But not everyone was a fan of Blitzstein’s work. Like Copland, the composer was called to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, where he admitted to being a member of the Communist Party until 1949, but refused to name other names or cooperate further.

Unlike Copland, Blitzstein is relatively unfamiliar to audiences today. And while this is likely for a myriad of reasons, some suggest that it was also because he was freely open with the same parts of his identity that Copland sought to make more private. In an era when it was neither popular to be gay or communist, Blitzstein was both. It may have impacted his legacy, and it eventually led to his untimely death in 1964 at the hand of three sailors, one who claimed that Blitzstein propositioned him.

The Debate Continues

It’s been a over a century since the Haymarket Affair, and the United States still grapples with these same issues, both politically and musically. A push for a $15 federal minimum wage has become a focus for Democratic presidential hopefuls in 2020. President Trump has pledged his support for American workers, while his relationship with unions has been fraught.

Like every president since Eisenhower, Trump re-proclaimed Loyalty Day during the first May of his presidency.

In this climate, both new and old music oriented around labor politics maintains its relevance. Over the years conservative politicians have evoked Coplandism, sometimes ironically, in their campaign ads. Bliztstein’s Cradlecontinues to be staged all over the country; Nashville Opera will perform it next weekend. Unions continue to be a powerful tool for classical musicians, illustrated this week as the Chicago Symphony Orchestra negotiated a new contract after a seven-week strike— the longest in CSO history. Less than two miles from the Chicago Symphony Center stands the Haymarket Memorial.

Chicago in particular is still reckoning with the legacy of Haymarket, including through music. In 2016 composer David Kornfield and writer Alex Higgin-Houser debuted their song cycle “Haymarket: The Anarchist’s Songbook.” Chicago Tribune critic Chris Jones described it as a “series of musical meditations on the lives and times of the anarchists” who were convicted after the bombing.

“Rise Up,” from “Haymarket: The Anarchist’s Songbook”

But in a larger sense, Jones points out that the song cycle sees Haymarket as a early indicator for an issue that fuels today’s protesters all over the country: the lives of the uber-rich 1 percent vs. the struggles of the working class.

Regardless of what you celebrate on May 1st, a debate that has lasted well over a century continues to unfold. And as it does, it might be wise to keep an ear on the music written about it.