“Short, short, short, long” is not so exciting when you read it out in words. But for composers Ludwig van Beethoven and Christopher Rouse, it was fate set to music.

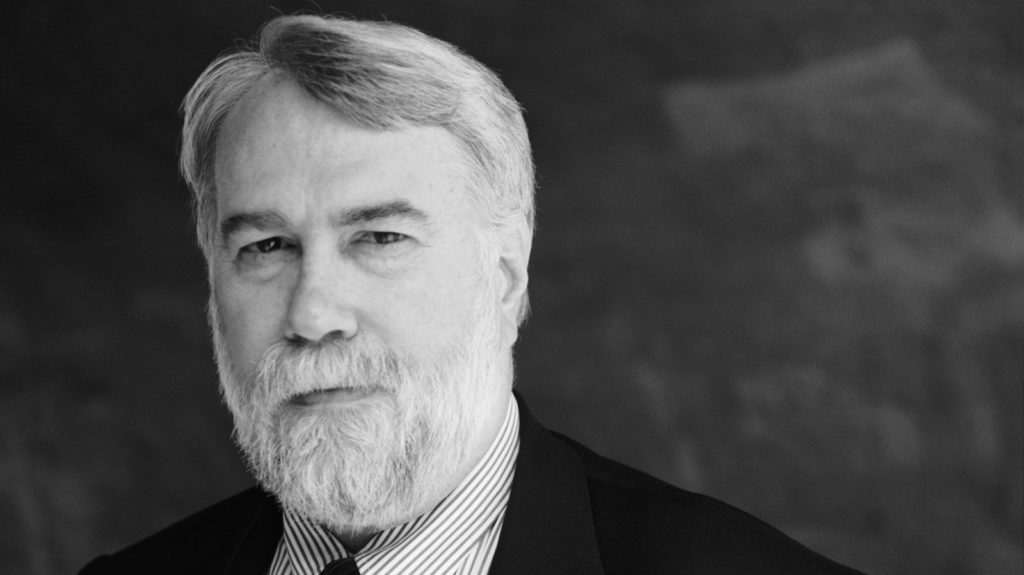

Pulitzer Prize and Grammy Award winner Christopher Rouse sat down with host Colleen Phelps to discuss his Fifth Symphony, and with that the process of commissioning new music for orchestra. Plus, the two compare Rouse’s fifth with Ludwig van Beethoven’s iconic Symphony No. 5, Op.67 and broke down where the composer looks for inspiration for his music.

One piece of Christopher Rouse’s interview that was mentioned in passing was the influence that the previous generation of American symphonists has had on his music. Here is a collection of music by these composers.

William Schuman: Chester

Like Rouse, William Schuman started his musical life in a band — albeit, a jazz ensemble where he played violin. He was known for bringing that jazz influence to works of every formal genre of the early 20th century Chester is the third of a set of pieces called New England Tryptich — all based on tunes by William Billings. The piece was originally written for orchestra, but Schuman immediately reorchestrated Chester for wind ensemble right after it premiered. And, unusually, he expanded the piece in the wind ensemble version.

Roger Sessions: Divertimento

Like several composers of his time (most notably Stravinsky) the music of Roger Sessions made a major harmonic shift in the mid 1940s. While Sessions liberally applied atonal harmony, very little of his output is in a strict twelve-tone style. On top of composing Sessions was a noted teacher — his students included Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, John Adams, Milton Babbit, John Harbison, and Frederic Rzewski.

Walter Piston: Concertino for Piano and Chamber Orchestra

Many conservatory-educated musicians are familiar with the textbooks of Walter Piston, including Harmony, Counterpoint, and Orchestration. After studying with Nadia Boulanger, French neo-classicism and infatuation with jazz colored Piston’s music. The Concertino for Piano and Chamber Orchestra marked the start of two decades of nearly unbroken output from the composer.

Vincent Persichetti: Pageant

By age 16 Vincent Persichetti was a self-sufficient musician – appointed music director of a Philadelphia Church, and a regular accompanist on the radio. By age 20 he was head of the music department at Combs College while simultaneously pursuing a degree in conducting at the Curtis Institute and degrees in piano and composition at the Philadelphia Conservatory. Pageant was Persichetti’s third band work. It begins slowly, but with the entrance of the snare drum picks up into a polytonal parade.

John Barnes Chance: Incantation and Dance

Many of the works of John Barnes Chance are played by high school age ensembles every spring. He began his compositional career at the Ford Foundation Young Composers Project in Greensboro, NC. Incantation and Dance is the earliest piece in his surprisingly small catalog — cut short by his sudden death at age 39.

Samuel Barber: Second Essay for Orchestra

The music of Samuel Barber is often described as neo-romantic. He often took influence from literary forms, as is the case with his essays for orchestra. The First Essay premiered at the same concert as Barber’s famed Adagio for Strings, and the Second Essay was sketched out at the same time as the Violin Concerto. The entirety of the Second Essay includes a gradual crescendo to a rather ecstatic finish.

Charles Ives: Country Band March

Charles Ives had a way of painting a musical picture of American life. From the quiet of a New England church to a Yale-Princeton football game, the tone poems were evocative to the last detail. Country Band March is no exception, as Ives gives you the musical image of two country marching bands, running directly into each other. They break ranks as they cross paths, and then go their separate ways.

Aaron Copland: Music for the Theater

Known as the “Dean of American Composers,” Copland’s pieces are some of the most recognized works of American orchestral music. His first workshop for this all-American sound was Music for the Theater. Each of the five movements explores a different mood to be evoked by the chamber orchestra. The texture: single melodies over accompaniment — is less formal than the counterpoint he had learned from Boulanger, and instead influenced by jazz.

Christopher Rouse: Der Gerettete Alberich

And for comparison, music of Christopher Rouse himself. This percussion concerto was concieved as a sequel to Wagner’s Ring Cycle – allowing Alberich to have the last word.