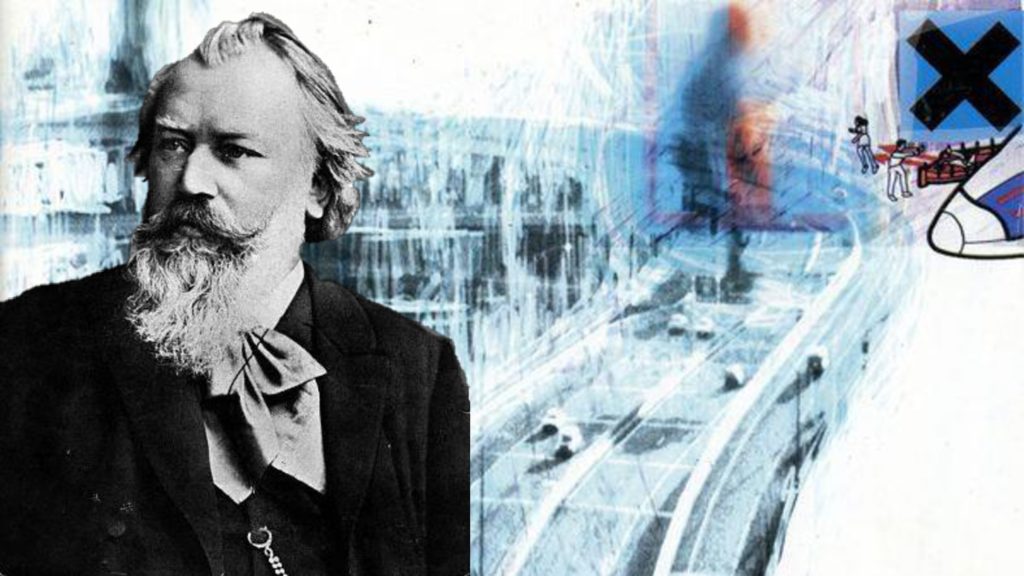

What do 19th century Romantic-era composer Johannes Brahms and modern alt-rockers Radiohead have in common? A lot more that you might think, according to Steve Hackman.

The young conductor, composer and all-around musician has been making a name for himself in recent years with his orchestral “mash-ups,” which seek to synthesize well known and well loved orchestral and pop masterworks.

This Sunday, Hackman will lead the Nashville Symphony with guest vocalists in an interwoven performance of Brahms’s First Symphony (which premiered in 1876) and Radiohead’s 1997 album OK Computer.

While the two works are separated by over a century, Hackman sees both musical and aesthetic similarities between them.

When speaking about those similarities, he becomes animated and verbose. “Sorry I’m talking so much,” he apologizes over the phone. “I’ve got a premiere tonight and the adrenaline has already kicked in.” He’s referring to his newest mash-up, this one between Tchaikovsky and hip-hop chart-topper Drake, to be performed by the Pittsburgh Symphony.

While some of Hackman’s musical combinations have been, self-admittedly, more successful than others (he’s also fused Beethoven with Coldplay, Bartók with Björk, and Copland with Bon Iver), Radiohead v. Brahms was the first large-scale mash-up that he says “just worked.”

On his dressing room piano, he picks out the first few arpeggios of Radiohead’s “No Surprises,” a track from the back half of OK Computer. “I don’t know if you can hear this,” he says as he hovers over the last chord of the song’s opening phrase, “but it pops up in the Brahms, too.”

He ventures a bit into theory and chord structure and explains that this particular chord (which happens to be a minor four chord with an added sixth) serves as one of the “musical anchor points” that made his fusion of Brahms and Radiohead possible.

Perhaps just as important as the musical similarities — which also include relationships in key and meter — are the aesthetic similarities. Hackman describes the Brahms symphony as brooding, weighty and tightly-wound, but with wonderful releases. “You can feel the 20 years it took [Brahms] to complete it,” he emphasizes. A similar moody restlessness pervades OK Computer, which critics at the time lauded as a snapshot of the anxieties of society at the onslaught of the information age.

As for critics of his mash-ups, Hackman says there are plenty. Save for a few Radiohead purists commenting on his YouTube account, he says most of the criticism comes from the classical side: “There’d be a problem if classical performers or audiences didn’t take issue with me ‘messing’ with Brahms. It’s sacred. It’s certainly not for everybody.”

He also says that mash-ups are “old news” in the world of popular music and probably less likely to ruffle any feathers — although, after a pause, he does mention Bartók’s penchant for infusing popular folk tunes into his classical compositions. Perhaps classical mash-ups are old news, too.

Hackman says he’s thrilled to have found so many established and reputable symphonies willing to take chances with classical music. He sees his mash-ups as an opportunity to engage a new generation of listeners that have yet to discover the likes of Brahms. Or, conversely, classical aficionados who know very little about Radiohead.

Either way, he emphasizes his respect and admiration for both musical works and his excitement over hearing each through an “elaborate, decadent and magnificent new lens.”