While Nashville has no shortage of boutique accommodations, a new hotel that opened in Midtown this month hopes to offer guests at least one unique experience: karaoke with an animatronic band. Today guests can belt out classics like Guns N’ Roses’ Sweet Child O’ Mine with a trio of Chuck E. Cheese-style robot musicians, but mixing music and mechanics is a practice that dates back to at least the Middle Ages. Here are a few notable examples of androids that have been programmed to perform:

Ismail Al-Jazari and his Floating Quartet

An illustration of Al-Jazari’s robot band.Wikimedia Commons

Sometimes referred to today as the “father of robotics,” polymath Ismail Al-Jazari was born in modern-day Turkey in 1136. His work as a scholar, inventor, mechanical engineer, mathematician and artisan lead to his publication of The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, which contained instructions and illustrations of 100 of his own inventions. One of Al-Jazari’s most elaborate creations was a band of four hydro-powered musical robots, meant to float on a lake and entertain party guests during royal festivities. Since Al-Jazari equipped his robot drummer with moveable pegs that defined its rhythm, the band may also be one of the first examples of programmable automatons.

Jacques de Vaucanson, The Flute Player

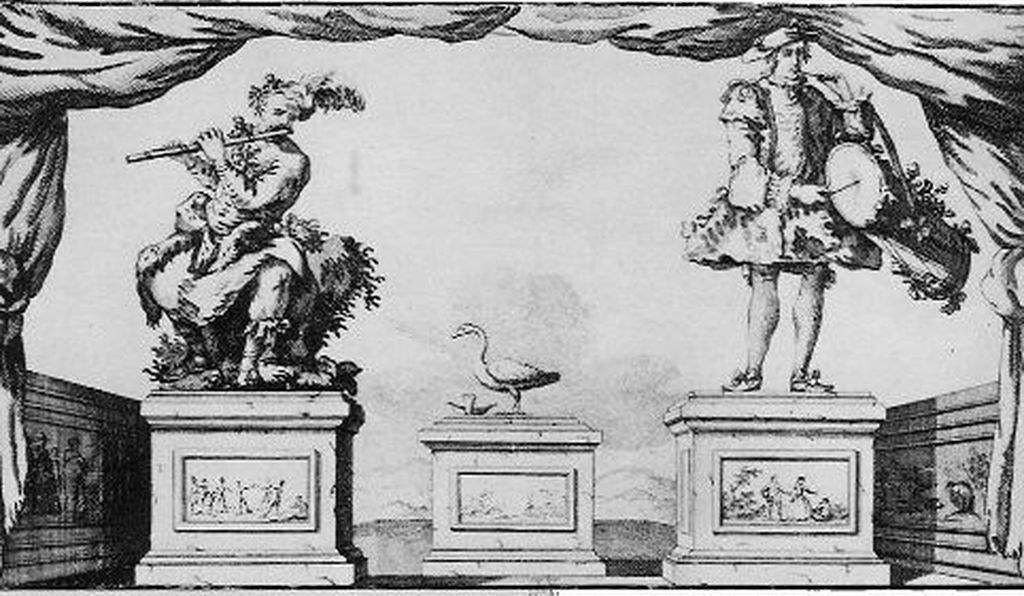

Vaucanson’s trio of automata: The Flute Player, The Digesting Duck, and the Tambourine PlayerWikimedia Commons

In 1737, French engineer and inventor Jacques de Vaucanson completed what is considered by many to be the world’s first true robot. The life-size figure stood over 5’8” tall, was carved from wood, leather and cardboard, and played a repertoire of 12 songs on a real transverse flute. The Flute Player, as the automaton was named, could move its mouth, tongue and fingers, leading Vaucanson to present a report to the French Academy of Science asserting that his creation could play exactly like a living, breathing musician. While the Academy was impressed, one person who took issue with Vaucanson’s claim was the long-time flute instructor to Frederick II of Prussia, Johannes Joachim Quantz. Quantz, perhaps a little unnerved by his new robotic competition, pointed out that The Flute Player could not move its lips properly. Instead, it relied on increased air pressure reach the instrument’s upper octaves, resulting in shrill tones.

Pierre Jaquet-Droz, The Musician

Jaquet-Droz’s The Musician

While The Flute Player is no longer with us, an organ-playing automaton built by Pierre Jaquet-Droz around 1770 is still performing at a museum in Switzerland today. The Musician plays her own custom organ by pressing the keys with a set of dextrous wooden fingers, while seemingly following her hands with her head and eyes. The intricate creation was actually a marketing ploy— Jaquet-Droz was a watchmaker, and was looking to sell his line of intricate mechanical bird watches, which you can still purchase today. Below is a short film about Jaquet-Droz and his automata, with The Musician appearing at the 6:30 mark.

Wolfgang von Kempelen’s Speaking Machine

If you haven’t already gotten the heebie-jeebies from old-timey flute and organ-playing robots, take a look (or rather, a listen) to Wolfgang von Kempelen’s Speaking Machine. While not technically a robot in the sense that it requires a human to operate a set of bellows, the speaking machine was Kempelen’s attempt to replicate human vocal cords and produce synthentic speech-like sounds. Kempelen spent two decades tweaking and refining his design, although his quest to produce a machine that could “sing” with variable pitches was ultimately unsuccessful. Perhaps Kempelen’s biggest contribution to society came several decades after his death in 1804, when a young Alexander Graham Bell saw a replica of Kempelen’s Speaking Machine at an exhibition and felt inspired to create his own version. Bell’s experiments with the speaking machine would eventually lead him to invent the telephone in 1876.

The Logos Robot Orchestra

Why settle for one musical automaton when you can have an entire orchestra? That’s the ethos of the Logos Foundation, an artistic organization that has assembled the world’s largest robotic orchestra. The 73-piece ensemble includes everything from player pianos and organs to an automated set of cowbells. Many of the robots have cheeky names— “Simba” plays the cymbals while “Bono” is an automated valve trombone— and Logos has detailed the capabilities of each automaton for potential composers. Before the orchestra becomes self-aware and seeks world domination, one robotic symphony at a time, listen to them perform a work by composer Kristof Lauwers: