This weekend, the Nashville Symphony is playing movie-related music from composers you may not associate with the cinema: Leonard Bernstein’s soundtrack to On the Waterfront, a suite of tunes from Prokofiev’s score to the Russian film Lietenant Kije, and a violin concerto in which Eric Korngold quotes melodies from his own film score.

Those three are far from the only “classical” composers to try their hand at writing for the big screen. Here are a few notable crossovers:

Camille Saint-Saens

In 1908, Saint-Saens wrote the first documented movie score for the French film Asassination of Duc de Guise. The movie was revolutionary in several ways. At a time when many films simply showed things like tableaus of beautiful scenery or dance routines, Asassination depicted a lurid story from French history.

It was long for the era, clocking in at 15 minutes. And instead of picking some preexisting music to have instrumentalists play during screenings, director Andre Calmettes asked one of the most prominent composers to write an original, fully orchestrated score tied to the action on the screen.

The 73-year-old Saint-Saens is said to have painstakingly coordinated his composition to the film’s narrative. However, he may have never witnessed its performance; the Paris premiere happened after he’d already left to winter elsewhere.

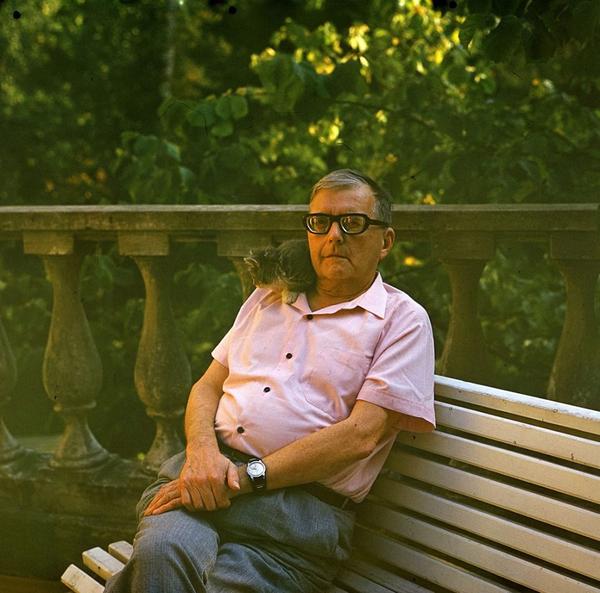

Dmitri Shostakovich

Shostakovich genuinely appreciated cinema as an art form. Selections from his score for the Russian film, The Gadfly have found continued life as concert pieces. His music for the Maxim triology, films made by friends of his, shows signs of the composer enjoying his work and playing with new musical ideas. But the bulk of the 34 films he scored were Stalinist propaganda pieces that he felt forced to write.

Shostakovich could hardly refuse the jobs, given that his position in Soviet Russia was tenuous. Stalin himself had loudly made fun of the composer’s music during a live performance in 1936. Shortly after, the newspaper Pravda published a series of articles denouncing his music.

That criticism coincided with the start of the “Great Terror,” Stalin’s purge of political and ideological enemies. While the composer was spared, a number of his friends and family members were imprisoned or killed. He spent the rest of his career walking a tightrope between artistic expression and political caution.

Philip Glass

By the mid-50s, a divide seemed to have settled in among composers: they tended to either write for movies or the concert hall, but few tackled both.

The more avant-garde a composer, the less likely he or she would ever purposely contribute to a film (even though filmmakers were certainly using existing compositions in their soundtracks). That was largely true of Philip Glass until he had a chance to view the first reel of Godfrey Reggio’s experimental 1982 film, Koyaanisqatsi. The minimalist composer was drawn to the slow motion scenery and time lapse images, shown without dialogue.

Glass and Reggio ended up collaborating on what has been described as a “visual tone poem,” which led to another two films in the same vein. Glass later re-recorded a longer version of the Koyaanisqatsi score and released it as a standalone album. He’s now a regular composer of film scores, even writing for big budget studio pictures like last year’s Fantastic Four.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PirH8PADDgQ