Amid some of the more predictable pandemic- and protest-related topics trending on Twitter this week, an unexpected name joined the list: Beethoven.

With this year marking Beethoven’s 250th birthday, the composer has certainly been receiving even more attention than usual, but his current spike in Twitter popularity was about another idea entirely: that he was Black. As of Thursday afternoon, this tweet from Twitter user Alyssa had been liked by over 248,000 people.

Beethoven was black?? Lmfao y’all aint gonna hear the last of this from me

— Alyssa (@howtopless) June 16, 2020

It was just one of many Twitter reactions to Black Beethoven that ran the gamut, from astonishment to anger — with plenty of humorous memes mixed in. The topic gained so much traction that Newsweek weighed in.

The notion that Beethoven was Black is not a new idea, although it has for years been debunked by Black and non-Black musicologists alike. Dominique-René de Lerma, who dedicated his career to studying African American music, quashed theories of a Black Beethoven back in 1990.

Black scholars and music writers on Twitter have been echoing de Lerma’s conclusion to varying degrees, including a strong denouncement from musicologist Imani Danielle Mosley:

okay let me get this straight: “Beethoven is Black" is trending? HOW MANY TIMES DO WE HAVE TO GO OVER THIS? (god i wish @LindaHyphen were here) Linda wrote about this at length, i did a long tweet thread about this…he wasn't Black, folks.

— dr little ferret, phd (@imanimosley) June 18, 2020

And a lighter rebuff from WQXR’s James Bennett:

“Beethoven was black and his whiteness is a cover up” is top 3 conspiracy theory (right up there with “Idaho isn’t real”) and the scholarship is “eh” BUT, MY PEOPLE:

KEEP.

THEM.

MEMES.

COMIN.— josquin dead prez (@jamesabennettii) June 18, 2020

de Lerma also detailed how the myth — which is fueled by the idea that Beethoven’s maternal ancestors came from a region of Europe that was ruled by the Spanish, and that the Moors from North Africa were part of this Spanish culture — has origins as far back as at least 1907.

That’s when Black composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor gave an interview in which he pondered the theory and supposedly remarked that were Beethoven still alive, “he would find it somewhat difficult, if not absolutely impossible, to obtain hotel accommodation in certain American cities.”

The idea continued to gain traction in the mid-20th century, when it was circulated by Black journalists like Joel Augustus Rogers and Carl J. Murphy. Music scholar Kira Thurman, who specializes in writing about Black musicians in Europe, posted a thread that included several clippings from Murphy:

Surprise! I can't answer that question yet. I haven't had time to go through original German sources and read them for myself. But I can tell you that the question, "Was Beethoven Black?" has been around since the 1930s, when African American journalists began to circulate it. pic.twitter.com/roDIToa196

— Dr. Kira Thurman (@kira_thurman) June 18, 2020

From there, Thurman says, Malcolm X picked up the idea in the 1960s, with the intent to “associate blackness with genius, which white people constantly denied.”

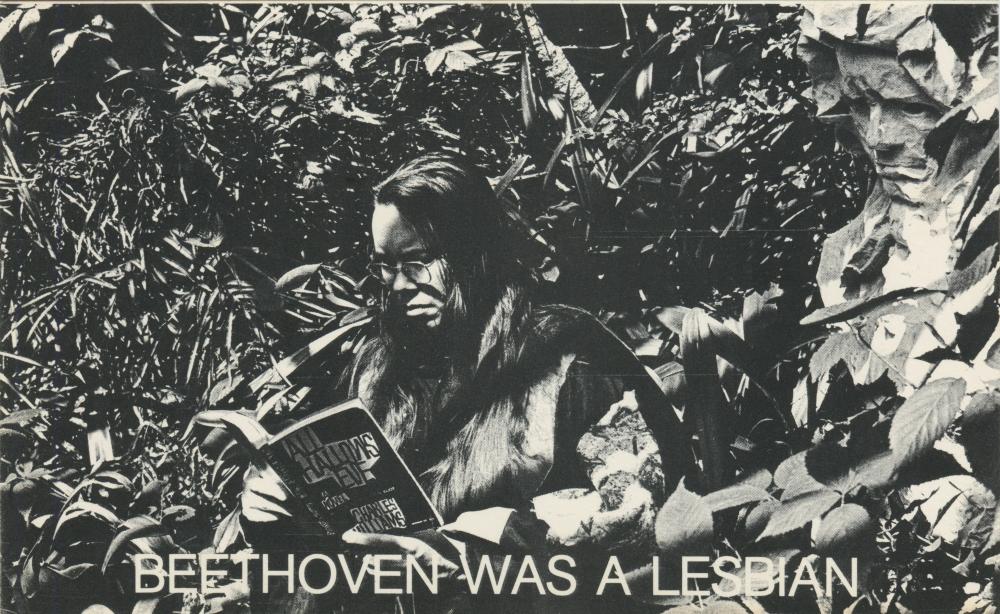

Asserting Beethoven as Black, then, served as an interrogation of a system predicated on exclusion. Pauline Oliveros did something similar in the 1970s with her “Beethoven was a Lesbian” postcard. Of course, in this instance, Oliveros knew that Beethoven wasn’t a lesbian, but in her performance art she asked audiences to imagine an alternate history confronting traditions that have largely excluded female and queer composers. In this sense, “Beethoven was Black” might do the same for composers of color.

“Beethoven was Lesbian” from “Postcard Theatre”

According to data from the Institute for Composer Diversity, professional orchestras in America still have a long way to go in diversifying their programming. In analysis of 120 orchestras, just 6% of music programmed for mainstage concerts in the 2019-2020 season was by composers from under-represented racial, ethnic and cultural heritages. In contrast, Beethoven alone accounted for 10.5% of programming, more than any other single composer.

In fact, representation is such an issue that even the Institute for Composer Diversity is being called problematic for its own lack of Black leaders and inadequate communication with Black musicians.

So what’s to be done? And does imagining a Black Beethoven really achieve anything?

In the Chicago Tribune late last year, Andrea Moore suggested a yearlong moratorium on Beethoven’s music during his 250th year, saying it would not only “give us a new way into hearing it live again,” but also create space for new music commissions. Or, space for under-programmed composers we know, without a doubt, are Black.

Kira Thurman continued her Twitter thread by asserting, “Instead of asking the question ‘Was Beethoven Black?,’ ask ‘Why don’t I know anything about George Bridgetower?’ I frankly don’t need any more debates about Beethoven’s blackness. But I do need people to play the music of Bridgetower. And others like him.” Bridgetower, a Black virtuoso violinist and composer, shared both a friendship and musical collaborations with Beethoven.

The late myth-busting musicologist Linda Shaver-Gleason posited in this post that instead of programming more diversity within a system already built around the “greatness” and “genius” of white European men, we create a new system entirely: “Centuries of white bias cannot be overcome by a few non-white, non-men sprinkled throughout a season … confronting white supremacy in classical music culture requires radically new approaches to how music is presented to listeners.”

It’s a sentiment shared by Nicholas Rinehart, who wrote in detail about the history of the Black Beethoven trope while parsing through more recent implications of the debate in 2013. He ended with this:

This need to paint Beethoven black against all historical likelihood is, I think, a profound signal that the time has finally come to make a single, concerted, organized, rigorous, dynamic and robust effort at fundamentally reshaping the classical canon and reconsidering and reimagining the history of Western art music, period.

Rinehart said 2013 was finally the time for such radical change, but 2020 is shaping up to be a more likely contender. As Beethoven turns 250, we have a year in which the world is wrestling with issues of race by way of massive protests following the killing of George Floyd. We have a year in which a global pandemic has shuttered concert halls, forcing ensembles to entirely rethink what performance looks like.

Given the circumstances, perhaps a statement like “Beethoven was Black” is not such an unexpected topic to trend on Twitter after all.