The Russian imperial court of the 1760s is wickedly portrayed in Hulu’s new somewhat historical series The Great, which centers on Catherine The Great’s rise to power. In the show, which takes great liberty with historical truth in favor of raucous storytelling, the future empress’s enlightenment-inspired ideals face skepticism (to put it mildly) from her adopted country – reflecting the reality of Russia’s reaction to her priorities. That being said, Catherine the Great did succeed in advancing the fine arts throughout her reign, including music, and especially opera.

Catherine the Greatwikimedia commons

After the coup that removed her husband Peter III from power, Catherine the Great indulged in a ravenous taste for the arts – amassing a huge collection of visual art, as well as founding the Imperial Opera and Ballet.

Productions at the Bolshoi Kamenny Theater in St. Petersburg were known for luxury that far surpassed European opera houses. Catherine herself was an active writer, completing nine libretti. She wrote to her friend Voltaire that while her operas had weak plots, they had well-formed characters.

The Bolshoi Theater, which is still in use today.wikimedia commons

While the Russian fairytale opera was a common trope in the 19th century, Catherine was ahead of her time. One of her most lasting libretti, for The Story of Tsarevich Fevey, was set to music by Vasily Pashkevich, who had been court composer for Peter III. Pashkevich often quoted popular songs in his operas, which had a lasting influence on later Russian composers. But, for all his efforts, the next generation of Romanovs were not happy with his work and denied him a pension after firing him from the court.

Comic opera first appeared in Russia during this time as well. This specifically refers to what we now might call musical theater: dramas with some singing, which were popular in France, and made their way to Russia via touring troupes. The earliest Russian example of this was Aniuta by Alexei Lvov. At the time, however, the librettist would have been given the lion’s share of the credit – in this case, Mikhail Popov. The music for this piece is lost, but another work by Lvov became Russia’s national anthem for nearly a century. Tchaikovsky fans may recognize God Save the Czar from the end of the 1812 Overture.

It was a touring opera troupe that indirectly led composer Vincenzo Manfredini to the Russian court. After accompanying his brother, castrato Giovanni Manfredini, to a performance in St. Petersburg, an offer was made to Vincenzo to stay as maestro di capella for then prince Peter Fedorovich, who became Catherine II’s husband. After the coup that gave power to Catherine II, Manfredini was retained in the post of maestro of the court Italian opera company, but was quickly overshadowed by Baldasarre Galuppi. So, Manfredini found his own niche in composing for ballet – a genre that became a hallmark of the arts in Russia. He was also the harpsichord teacher to Prince Paul, the heir to the throne.

Baldassare Galuppi a.k.a Il BuranelloVenetian School of the 1750swikimedia commons

Baldassare Galuppi was not looking to leave his coveted position as maestro di capella at the duomo in Milan when in 1764 the empress of Russia used diplomatic channels to request his presence at her court. Without Galuppi’s consultation a deal was made that he would stay in Russia for three years, and as long as he provided St. Mark’s with a newly composed Gloria and Credo for Christmas masses, his position in Milan would be secure when he returned. Upon his arrival in Russia Galuppi made great improvements with the court orchestra, but arrived to what he considered a very impressive choir. While he was in Russia he composed some new works, but also conducted quite a bit of music he had already composed in Italy.

The play Le Barbier de Séville by Pierre Beaumarchais was first turned into an opera in Catherine II’s court, with music by Giovanni Paisiello. In fact, Paisiello’s version of the story outshined even Gioacchino Rossini’s opera decades later. Paisiello’s setting of Figaro’s story was the first opera production of Russian origin to become a sensation all over Europe.

Salon music also became popular in Russia, as it had been in France, during the latter half of the 18th century, as a new generation of composers reaped the benefits of newly available educational opportunities that had been advanced by Catherine II’s priorities, both in the arts and for women.

Princess Natalia Ivanovna Kourakia nee Golovina, painted by Marie Louise Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun.Utah Museum of Fine Artswikimedia commons

Through salons, Princess Natalia Kurakina became one of the most popular composers and performers of her time in Russia, performing for the court at the young age of fourteen. Kurakina became the most prolific Russian composer of the 18th century. When her husband fell out of favor during the reign of Alexander I, she was able to transfer her abilities to France, where she noted that the salons of Paris and St. Petersburg were nearly identical. Late in her life, on a visit to Paris, she met a very young Franz Liszt, who improvised a set of variations on one of her songs.

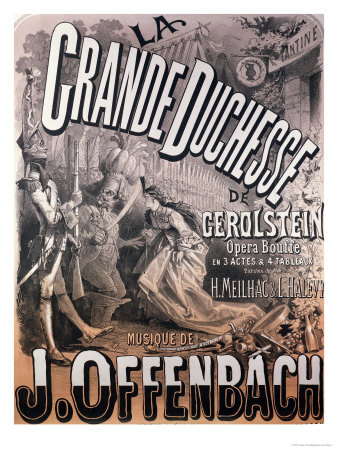

Publicity poster for Jacques Offenbach’s opera La Grande Duchesse.Jules Chéretwikimedia commons

A century after she took power, Catherine the Great was satirized in La Grande Duchesse de Gerolstein by Jacques Offenbach, which features a loveable but imposing regal figure, and a bumbling army that wins a battle by getting the enemy drunk.

These musical developments are even more remarkable when Russia’s history is taken into consideration. Repeated bans on secular music from the church as schism occurred even into the late 17th century seemed to trap music and culture in a time gone by. This preservation combined with a push toward westernization by Peter I and Catherine II led to a unique national voice in classical music.

Voltaire (Dustin Demri-Burns) greets Catherine (Elle Fanning) while Peter III (Nicholas Hoult) looks onOllie UptonHulu

Should The Great move on to a second season, we will hopefully see a sensationalized telling of the changes in the Russian court as art, literature, and music developed throughout the enlightenment. And perhaps a visit from Galuppi or Paisiello could be as influential and amusing as the first season’s advice-giving Voltaire.