Nobody told Glenn Gould to stop touring, or suggested he perform a digital concert. Why would they have? There wasn’t a global pandemic forcing performers to stay home in the 1960s. But Gould’s own distaste for the act of live performance led him to shun traditional concerts early on in his career. Now, as today’s classical musicians face long concert hall shutdowns head on, Gould’s mid-career turn to recordings and broadcast might act as one possible model for a way forward, at least for the time being.

More: Ludwig van Beethoven turns 250 this December.

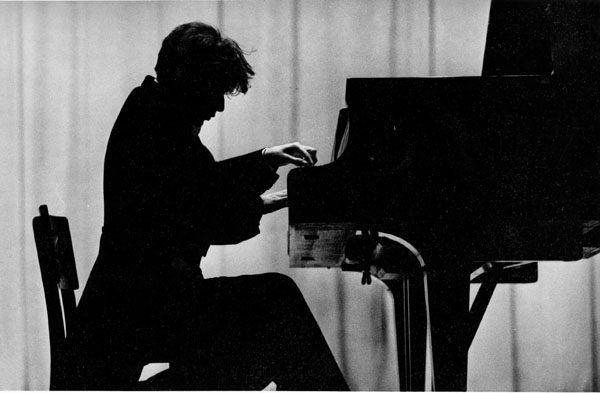

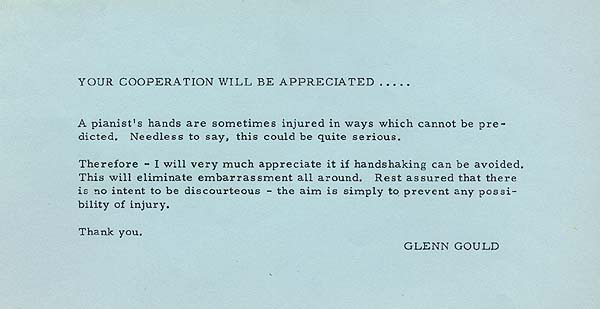

Glenn Gould’s virtuosic talent is often overshadowed by tales of his eccentricities. He sat very low at the keyboard, in a chair specially built for him by his father. Its squeaks combined with Gould’s humming provided constant hurdles for recording engineers. Gould was temperamental — he hated to be touched, and was so averse to cold that he often bundled up into excessive layers with the thermostat set uncomfortably high, which caused friction with his collaborators.

Glenn Gould’s polite request to avoid shaking handsLibrary and Archives Canada/Glenn Gould fondsEstate of Glenn Gould and Glenn Gould Limited

With all of his quirks, it’s not a surprise that he found a distaste for live performances as “anachronism” and a “force of evil” that he compared to a sports arena. In this interview with fellow Canadian Alex Trebek, Gould expressed his feelings on audiences quite frankly.

Indulging his feeling of discomfort, Gould instead developed what he called a “love affair with the microphone.” He focused his energies on the recording studio, as well as television and radio. In the early 1960s he began a series of piano recital broadcasts for Canada’s CBC, which he would introduce with intimate spoken commentary. Many of these performances featured music by Ludwig van Beethoven.

Gould’s recordings of the music of Beethoven were called “perverse” and “offensive” by some critics. It was a shock to hear the pianist do precisely the opposite of what Beethoven asks in places: slurs became detached, pianos became fortes, and a tempo could be cut nearly in half. While they may have disagreed with the artistic choices, the technical facility of the playing left little doubt that each departure from the traditional interpretations of Beethoven’s music was deliberate. Leonard Bernstein referred to it as a “search for truth” in Gould’s playing. These weren’t lazy or thoughtless performances—they were an iconoclast at work, both in albums, and on television.

If Glenn Gould had televised a traditional rendition of Beethoven’s music, then would we still be looking at it five decades later? Has any pianist since taken such bold liberties with Beethoven’s music?

Gould’s broadcast performances of these pieces, splitting the difference between the recording studio he loved so well and the concert hall he claimed to despise, shined a fresh and interesting light on several of the famed composer’s works.

Piano Sonata No. 17 “The Tempest”

“I’ve been told that I can have four minutes to say something original about Beethoven.”

Looking at his watch, with his necktie askew, and trying to remember the name of “my favorite cartoon character… who plays Beethoven on a miniature piano,” Gould marked the 140th anniversary of Beethoven’s death. He noted that Beethoven’s career marked a near midpoint in the entire classical repertoire. He suggested Beethoven as a “living metaphor for the entire creative condition”—one who honored tradition while romantically emoting and experimenting. Not unlike the view one can, in hindsight, take of Gould’s performances of Beethoven, and even Bach. Honoring the pieces’ history, placing them at the front of his practice, but holding very little within the performance instructions as sacred.

It’s ironic, in such a case, that Gould would mock John Cage, who agreed with the mission of breaking new ground, expressing that he never understood why people feared new ideas, as he was “afraid of the old ones.”

32 Variations on an Original Theme

What followed on that same concert broadcast was Beethoven’s 32 Variations on an Original Theme. Toward the end of his life Beethoven observed a friend practicing the piece. He famously asked, “Whose is that?” only to be told it was his own. Beethoven admitted his own folly, as the friend offered, “What an @#$ you were back then.”

While many pianists still debate Gould’s artistic decisions in this performance (once again a question of articulation and tempo) the visual display at the opening is a sight to behold. Gould seems to conduct himself and the piano, his hands drawing the sound upward from the keyboard, letting go of the keys much earlier than you’ll find in other performances. In doing so the theme turns into almost a French Overture, elegantly sauntering forward rather than singing. Before the exact opposite happens with the first variation.

Symphony No. 6, Transcribed by Franz Liszt

By intensely focusing time and energy on recording, Gould made history. He was the first pianist to record any of Franz Liszt’s transcriptions of Beethoven’s symphonies. Attempting to re-create the myriad of colors available to an orchestra on just one instrument seemed to be an appropriate challenge for a detail-oriented performer like Gould.

The sight of the pianist performing in an empty concert hall may seem stark, but it’s likely to become familiar to us before the end of this socially distanced season.

15 Variations and Fugue

There was an existing model for bringing classical music to television. NBC had broadcast Gian Carlo Menotti’s Amahl and the Night Visitors every Christmas Eve since 1951. Beginning in 1954, Leonard Bernstein’s show Omnibus had become a gold standard for the arts on television. In fact, Gould’s television debut was with Bernstein, playing Bach at age 28. The two became friends, and while Gould lacked Bernstein’s charisma, he shared a sincerity in his desire to share classical music with a more broad audience.

The first of Gould’s own CBC broadcasts was actually titled The Subject Is Beethoven, with a music theory pun hinting at a sense of whimsy rather than the serious analysis to which the audience was treated. More than in any of his other introductions, the 29 year old uses the piano to illustrate his points as he goes. The depth of his knowledge is apparent as he references so many other works by Beethoven that some music students may never open, such as The Creature of Prometheus.

Emperor Concerto

“Nowhere this side of Grand Old Opry can one encounter more unadorned II-V-I progressions.”

Young Glenn Gould performed about 250 concerts before “retiring” to the microphone, 90 of which included a concerto by Beethoven. Of the 18 times he performed the Emperor concerto, it was the last one that came completely by chance – well after he never meant to perform live again.

In 1970, for the 200th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth, the Toronto Symphony planned a televised gala concert, including the Emperor with Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli as the soloist. When a producer for the show described this plan to Gould, the pianist joked that he should possibly be ready to step in, given Michelangeli’s tendency to cancel.

This proved to be an astute joke, and it’s what led to Gould being called into service at the last minute, unrehearsed, to perform the piece. Conductor Karel Ancerl joked that the orchestra had “substituted one kook for another.”

During the performance, it’s easy to wonder if Gould actually missed concertizing. During a long stretch of waiting to play, watch the pianist’s face. He seems to genuinely enjoy hearing the piece from the best seat in the house.

We’ll be writing about Ludwig van Beethoven throughout the year, as we count down to the composer’s 250th birthday this December. Find all of our Beethoven content on our Beeethoven250 page.